Monty Hall

The Monty Hall problem is a classic game theory and probability puzzle that most people have heard of in their grade school mathematics classes. The problem comes from the TV show “Let’s Make A Deal” where a contestant is shown three closed doors. Behind one door is a prize, behind the other two doors are goats. The odds of choosing the prize in this scenario are 1 in 3. But there’s a catch, because after the contestant has chosen their door, the host Monty Hall, opens one of the goat doors revealing the goats. Now the contestant has a choice, they can keep the same door they’ve chosen or, they can switch doors. Now the probability is actually 2 in 3 but only if you switch doors. This is where the confusion lies for many people, the goats and prizes haven’t switched doors, yet somehow by switching doors you have better odds of winning the prize (unless you wanted goats).

The problem comes up so often because so many are fooled or confused by the seemingly simple looking problem. I should clarify that I mean many people, pigeons apparently, are not fooled by this problem, so I look forward to further experiments with pigeons and game shows.

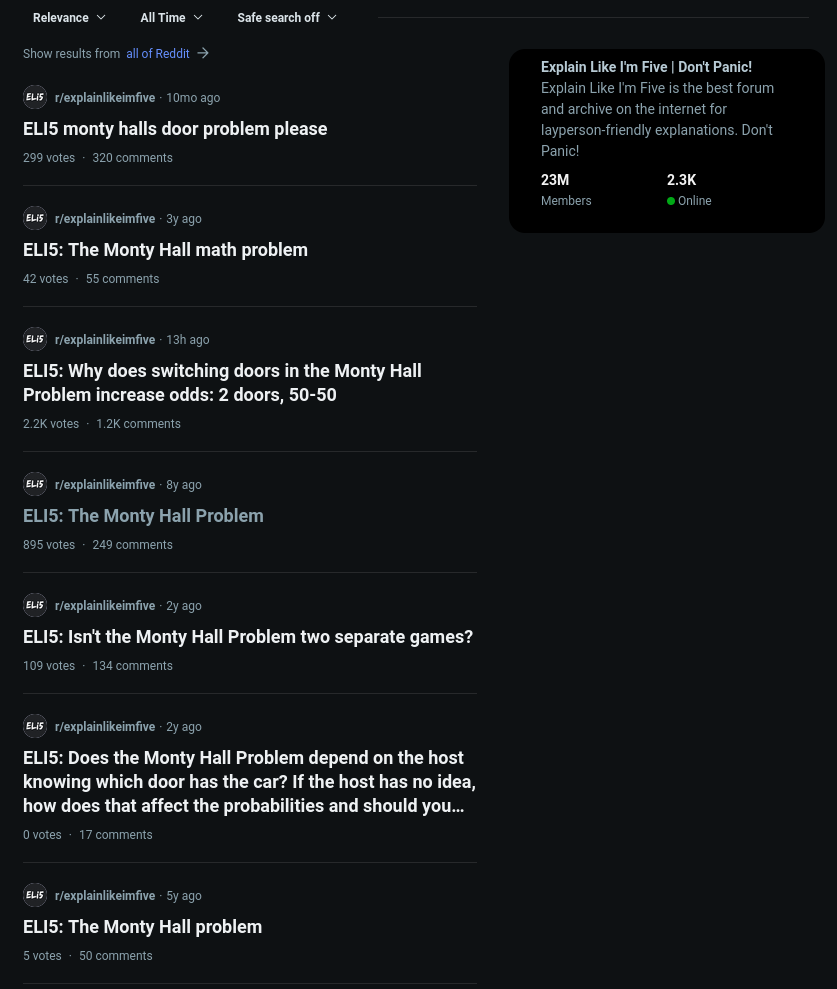

I’ve heard this problem dozens of times: math class, stats class, several computer science classes and on a TV sitcom. I’ve read several explanations of the problem and after seeing it posted on Reddit for probably the thousandth time where explanations alone don’t seem satisfying to some:

I thought I would sit down and simulate it instead.

Simulating the problem#

The code is pretty simple and you probably don’t need much time to throw it together. Here I simulate the game 100,000 times for each scenario. One where we switch doors every time, and one where we stick with the same choice.

import random

class Game:

def __init__(self, num=3) -> None:

self.number_of_doors = num

self.prize_door = random.randint(1, num)

self.door_chosen = None

self.remaining_doors = []

def pick_door(self, door):

self.door_chosen = door

def switch(self, will_switch):

if will_switch:

self.remaining_doors.remove(self.door_chosen)

self.door_chosen = self.remaining_doors[0]

def remove_doors(self):

# If the prize door and the chosen door are the same. We need need to keep some other non-winning door

if self.prize_door == self.door_chosen:

exclude = [self.prize_door]

other_door = random.choice(list(set([x for x in range(1, self.number_of_doors)]) - set(exclude)))

self.remaining_doors = [self.door_chosen, other_door]

else:

self.remaining_doors = [self.door_chosen, self.prize_door]

def is_winner(self):

return self.door_chosen == self.prize_door

def simulate(number_of_simulations):

total_wins_from_switching = 0

total_wins_from_not_switching = 0

number_of_starting_doors = 3

# Simulations where we switch doors

for _ in range(0, number_of_simulations):

monty = Game(number_of_starting_doors)

door_chosen = random.randint(1, number_of_starting_doors)

monty.pick_door(door_chosen)

monty.remove_doors()

# We always switch

monty.switch(True)

if monty.is_winner():

total_wins_from_switching += 1

# Simulations where we do not switch doors

for _ in range(0, number_of_simulations):

monty = Game(number_of_starting_doors)

door_chosen = random.randint(1, number_of_starting_doors)

monty.pick_door(door_chosen)

monty.remove_doors()

# We never switch

monty.switch(False)

if monty.is_winner():

total_wins_from_not_switching += 1

print(f"Win percentage where we switch {total_wins_from_switching / number_of_simulations}")

print(f"Win percentage where we do NOT switch {total_wins_from_not_switching / number_of_simulations}")

simulate(100000)

Running this gave me the results:

Win percentage where we switch 0.66599

Win percentage where we do NOT switch 0.3315

The odds are set when you make the choice for the door. The first time you choose you have a 1 in 3 chance. The second time, one door is removed and your chances go up to 2 in 3 because one of the doors is known to be incorrect, so switching will lead you to winning more often. You can make this even more apparent if you change the number of doors that you initially start with.

Lets say we start with 100 doors in this scenario. 99 goat doors and one prize door. After you’ve chosen one, we’ll show you all the other doors except for the chosen door and some other door.

+---------+ +---------+ +---------+ ... +---------+

| | | | | | | |

| Door 1 | | Door 2 | | Goat | | nth Goat|

| | | | | | | |

+---------+ +---------+ +---------+ ... +---------+

^

|

The chosen

door

I’ll make a small change to the code and make number_of_starting_doors = 100. When I simulate 100000 plays again I got the following results:

Win percentage where we switch 0.99012

Win percentage where we do NOT switch 0.00991

The first time we choose a door we have a 1 in 100 chance, that’s why the win percentage for not switching is ~1%. But choose again and we have a 99 in 100 chance if we switch. Better explained still, the first time you choose, you’re pretty unlikely to choose the correct door if there are 99 wrong doors. When we show all the goat doors but one however, we need to present the contestant a choice that includes the prize door so it’s very likely that the door we haven’t chosen is the correct door. The simulation and adding additional doors makes this much more obvious. When you choose to make the switch, it’s almost like you’re playing a second game. You’ve locked in the statistical probability the first time you chose a door so when we reduce the number of doors available to choose from you have a higher chance of winning by choosing to switch.

Further Reading#

- “Are Birds Smarter Than Mathematicians? Pigeons (Columba livia) Perform Optimally on a Version of the Monty Hall Dilemma” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3086893/